Earlier this month I spoke at the Westminster Education Forum Keynote Seminar:

The future for music education in England – maintaining standards, music hubs and career pathways, 3 rd July 2017, and my topic was:

Provision, uptake and teaching at primary and secondary level

I was given 5 minutes, which is not a lot of time to cover the ground, make relevant points, and discuss. I was in very esteemed company; the session was chaired by Rt Hon the Lord Wallace of Saltaire, who is a great advocate for music education, and other speakers included Darren Northcott, National Official, Education, NASUWT, Kevin Rogers, County Inspector, Hampshire County Council’s Music Service, Marie Bessant, Subject Specialist – Music and Performing Arts, OCR, Deborah Annetts, Chief Executive, Incorporated Society of Musicians, and Mark Phillips, Senior HMI, Ofsted. It was a charged and passionate group of speakers and delegates, discussing something dear to us all and fundamental to our children and our society. Below is my speech followed by some comments on the morning.

Here is what I said:

Thank you. My Lord, ladies and gentlemen, good morning.

Before addressing the take up provision, and what we’re doing about music education, the first question we need to ask is, why, why are we teaching music? Some of these children will grow up to be musicians. However, all can benefit in their future careers, from a strong music education. The value, impact, and implications of what music teaches is not always understood. These values lie at the heart of the National Curriculum, where music facilities independent enquiry, self-management, creative thinking, effective participation in collaborations, team working, and reflective learning. This ethos was echoed by the pedagogue Suzuki, when he said, “Teaching music is not my main purpose, I want to make good citizens, noble human beings”.

Today’s students are under great pressure to achieve on tests, to be measured. Music is seldom included in the understanding of progression via test scores, in the same way as numeracy and literacy subjects. Has the perceived value of music changed over time to parents and schools in light of tests? I hope not. But the focus of the music provision has changed. Music hubs were set up at a time when the funding model changed dramatically, to ensure that all students retained the opportunity to learn music.

The goals of music hubs, as set out by the DfE, and the DCMS, in 2011, were to ensure that every child had the opportunity to learn a musical instrument, ideally for a year, but at least for a term on that same instrument. To provide opportunities to play in ensembles, and to perform from an early stage. To ensure that clear progression routes are available, and affordable, to all. And to develop a singing strategy, to ensure very pupil is singing regularly, and that choirs, and other vocal ensembles are available. This is very difficult to provide for all.

That includes students:

- who already play instruments,

- who would like to start learning an instrument,

- who want a more informal approach to learning music, like playing in a band with their peers, and also

- those who are not interested in formal study, but are interested in listening to music, and informal enjoying.

There are pressures on effective delivery facing primary and secondary schools; cost is the obvious one. Being subject to changeable Government policies on certain funding, dependency on school buy in, and relying on parental contributions, means primary schools are unable to spend money on specialists, when facing cuts in their core teaching staff.

Much of these provisions used to be delivered my music specialists, now they’re often outsourced. There’s a cost to schools, and this means a strain on what can be offered. Outsourcing music provision is like a patch. For schools, the buy in of hubs also ticks that box of the National Curriculum. Many schools cannot afford the buy in. Though last year West Sussex Music taught 8,700 children, across 137 schools in whole class tuition, that is still a small percentage of the children overall, and covers under half of the area schools. My local primary school lost their music specialist, and only maintains a class provision for a single year group, one class of children, by fundraising through their parent association. Otherwise, the headteacher has confirmed, music would be squeezed out completely.

There’s a dichotomy, whole group tuition has the widest reach, but last year demand for private lessons, from parents and pupils from West Sussex Music, was up 30%. Class sizes are set to grow, magnifying the challenges of inclusion. Teaching 30 to 40 children an instrument at once, means careful organisation, coordination, and communication. Imagine 30 of you, all learning the violin or the clarinet, in one group.

As numbers grow, inclusion becomes even more challenging, yet preserving an introduction to music making is essential. Secondary schools, face the challenge of teaching a hugely diverse student body, from the post-grade eight student, to those who’ve never touched an instrument. Teacher responsibilities are multi-disciplinary, a portfolio career needs portfolio training.

So what are we doing about it? Addressing the future workforce, to enable them to deliver a well-rounded music education. My university students work with employers and schools, with placements, shadowing and gaining paid apprenticeship positions with providers, like West Sussex Music, as they work to reach ever wider audiences of children. At Chichester, we’re aware of what’s happening across our local primary and secondary school networks. We need to prepare our graduates to be malleable, innovative, and highly skilled. As school leavers are looking forward towards higher education, those people want to study music. At Chichester, we have more than 1,000 undergraduates in the music department, and there are six applications for every single place on our Musical Theatre Degrees. We have unique Music with Teaching Degrees. We’re looking to add a top up PGCE year, to add QTS status to the grounding our graduates already receive in individual and group teaching curriculum design, and private studio management.

People equipped with specialist knowledge, to deliver instrumental tuition, national curriculum music, and use their specialist instrumental vocal teaching skills to enhance the delivery of other core subjects, are desirable teachers. In continuing to bridge these gaps, from primary school through to university, through partnership and creative thinking, our graduates will keep music in their future, and in the futures of our children.

Thank you.

____________________________________

A few comments on the morning:

Marie was very respected by the floor and had a large part in personally writing the GCSE curriculum. She spoke genuinely and the floor was pleased that she said to ‘teach the music first’, but I was surprised when she added [that one should] think about the assessment later, as students will ‘accidentally be picking up’ what an exam board assesses. I am sure she did not mean just that; assessments don’t generally just happen. During the morning’s speeches, we were all strictly limited in time and often there were responses to questions and comments that the panel were dying to contribute, but there wasn’t time, and the agenda moved on to the next speaker. Learning, general musical engagement, musicality, and even developing public performance skills are very different to learning to jump through the hoops for a criteria based assessment, whether GCSE or externally graded exam. A student might pass, but unless the teaching specifically has those criteria in mind as a way of demonstrating learning outcomes, you could miss the mark significantly. On the Music with Teaching degree at Chichester, there is a specific module to teach the distinction between performance and assessment where students learn a new instrument to Grade 1 standard and sit a mock exam, and also give public performances (on their main instrument). They are assessed both on performance and on reflections about the differences in the learning and performing experiences.

As Mark Phillips began to speak I was already slightly guarded. I was Vice-Chair of my Primary School’s Board of Governors when Ofsted came, and I remember trying to anticipate the questions and wondering what they were trying to unpick as they asked and asked and then stopped. I wondered why they stopped asking, it was cryptic and I began listening with that experience at the back of my mind. However, that instantly melted, and what Mark said, his attitude, and genuine belief and concern for education and the future of music really resonated and stuck with me.

It was from his talk that I scrawled notes on my paper:

“Data gives you the questions to ask, it doesn’t give you the answers.”

Yes, I thought. Yes indeed. He went on…

“Curriculum is about education, it’s not about subjects”

He had a catchy three word saying about curriculum:

Intent, Implementation, Impact

and finally “Assessment measures whether you are meeting your intentions,” which took me back to the point about teaching to the test. Oh, I do not advocate that! Assessment and getting caught up with teaching to a test opens a can of something worse than worms, and it does impact all of us (in education). Even now I have a cohort of students worrying about their essays… Fortunately communicating clearly is one of the skills they are learning, and therefore assessed on, but it does not detract from the unbalanced stress placed on preparing ‘that task’. At the core of it, we as educators need to be clear what are the intentions for learning and how can those be assessed (demonstrated).

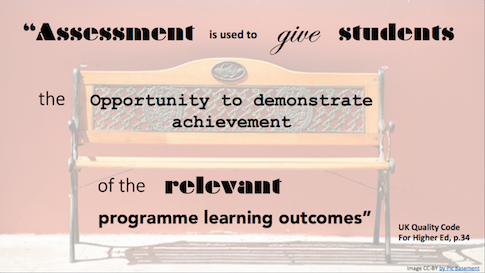

I am reminded of a quote from the UK Quality Code for HE:

(I loved the quote so much I made it look nice.)

(I loved the quote so much I made it look nice.)

There are no easy answers, and one thing that clearly came out of the event is that this needs to be discussed and addressed by musicians (students and teachers) and educators at all levels. Music education is not something we can let dissolve slowly. One delegate suggested that if every music student, parent/guardian of music students, and teacher across the country stood up for music education… He suggested a strike type demonstration, but I am sure that something more outwardly positive and participatory where everyone came together and SANG and PLAYED their instruments and CHEERED…. People would notice. Policy makers would notice. And there would be music in the air. A national holiday for music? Ok, now I’m dreaming… but still

I’d be there.