“For instruction to be most efficacious, a realistic curriculum is essential. What a curriculum does is organise and sequence the vast number of music experiences that lead to musical understanding and expertise in performing, listening, knowing, analysing, and enjoying.” (Colwell, 2011, p.128)

Planning and the rationale for what is taught is about connecting it up, and part of connecting the dots involves the teacher having the vision that outlines a curriculum for the student. (featured image CC licensed: http://bit.ly/1ovgFuS )

Resources to use:

Many books and articles focus on curriculum planning for academic lessons in school settings. These often include criterial references that take the teacher through a series of checks to ensure that various fundamental skills are being taught. Few specific texts advise specifically on how, what, and why a private teacher should teach. Richard Colwell reinforces this in his chapter ‘The roles of direct instruction, critical thinking, and transfer, in the design of curriculum for music learning’ within the MENC Handbook of Research on Music Learning Vol.1:

“Discipline specific pedagogical content knowledge looks like a list of habits of mind, consisting of skills, sensibilities, and judgements, as well as knowledge. Deep mathematical knowledge by itself, as it is in music, is inadequate preparation for teaching or for curriculum construction.” p.125

As a model that works to enable the connections that develop understanding, Marzano and Kendall (2007) suggest a teaching structure that includes four stages:Retrieval, Comprehension, Analysis, and Use.

- Retrieval: recognise and recall information

- Comprehension: understand connections and attribute meaning to information

- Analysis: classification and decoding of information

- Use: practically demonstrate through performance

Task:

Read pp.125-130 in the MENC Handbook of Research on Music Learning: Volume 1: Strategies edited by Richard Colwell and Peter R. Webster (link takes you right to the page)

Of course when planning any curriculum there need to be connections. There needs to be a rationale. Careful consideration of what to include will be based on each student, their experience, goals, understanding, and approach to learning will be different and every instrument comes with its own technical and musical challenges. As far as the connection, we need to begin by initially considering both the student and the content. Other considerations will be added to this list, like the interaction and reflection in delivery and the student’s time away from the teacher between lessons, but for now this is our beginning.

The content:

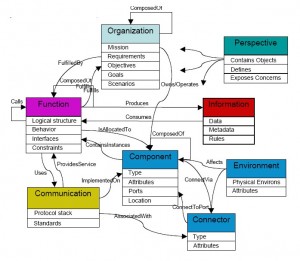

Sometimes the map that results from planning gets so complicated that although it makes perfect sense to the specialist, as in this “MBED Top Level Ontology” by Peter Shames & Joseph Skipper. NASA, JPL. – “Toward a Framework for Modeling Space Systems Architectures”:

CC Licensed: http://bit.ly/1tL32d2

to a student who has never seen it, that same map can feel more like a mess of spaghetti.

CC Licensed: http://bit.ly/1wknkrQ

Connections are fundamental to communicating and maintaining student interest through the course of lessons. Kieran Egan focuses on areas that are sometimes overlooked when planning is concerned. Plans tend to be drawn out in the form of firm schematics. There is nothing wrong with that if you are building a ship, but when dealing with people, and potentially a different learner each time the lesson is taught, then a different approach needs to be taken.

Connection as Storytelling:

The tradition of music is primarily aural, even though there are many musicians read scores. Music is made through sound. Music is sound, and even score-reading musicians work to get the music ‘off the page’. Through this aural tradition, there are other links and associations that music practitioners can draw upon and borrow. Egan explains how storytelling fits into that sonic picture:

“Among the significant differences which have received a considerable amount of attention recently are those due to writing. In oral cultures there are no ways of maintaining the kind of artificial or cumulative “memory,” and associated forms of thought, common in literate cultures. In oral cultures the lore of the social group has to be preserved in living memories. This places a high social value on those techniques which aid the preservation of knowledge in memories. So such techniques as rhyme and rhythm are important in communicating the culture’s lore, because they aid the effectiveness of its memorization. Next formulae also play an important role. But perhaps the most important of all the techniques developed in oral cultures is the story. If one can encode the lore to be remembered into a story, it has been found universally, then one can more securely fix it into other minds. This is because the story can attach emotional orientations to the elements that make it up; that is, the story can not only convey the lore of the culture but can do so in a way that encourages emotional commitments to it. If the encoding of the lore can be achieved metaphorically in terms of vivid and dramatic events, with weird creatures performing outlandish acts, then the memorability is even further increased. These are some of the typical characteristics found in myth stories around the world.

So rhyme, rhythm, meter, formulae, metaphor, and story are techniques of considerable social importance for the preservation of the memory and sense of identity, and also social relationships, economic activities, and so on, of oral cultures. It is not my intention to elaborate on these here in the context of oral cultures (see e.g., Havelock, 1963, 1986; Ong, 1982; Goody, 1977, 1987).” P.13 from Teaching as Storytelling (supplemental material)

He explains how imagination and humour impact the enjoyment of storytelling. In this short video Egan demonstrates how he can engage a listener by adding a slight twist:

Task:

-

Read K. Egan’s supplemental text: Teaching as Storytelling

-

Does this make you reorient your view of the student?

-

How might you adapt your teaching approach?

-

-

Look through these tips for creating fantastic stories: The 22 Rules to Perfect Storytelling, According to Pixar

-

Tell the story of your journey home after work, class, or wherever you spend your day. Use some of the ideas in both readings. Write it down and articulate the structure and the connectedness of the thoughts, happenings, and experiences. Have at least one character. There are no rules. It does not have to be based in or on reality. Share it somewhere that others can find it if they look for #MUS654 or leave it in a comment on this page!

Relating it to Music:

Kirsten Bartlett is a music teacher in California who has blogged a description of the components within the vocal curriculum she teaches. In the post there are dozens of references to academic articles and publications that support the underlying need for each aspect of learning. Although it does not provide a set list of what will happen when, the template categories would be hard to argue with as important to include in the curriculum of any musician.

Task:

-

Read Kirsten’s blogpost Private Vocal Lessons: A Curriculum

The student:

In Egan’s supplemental chapter he discusses the understanding of children and children’s understanding and how these can be woven into using aural traditions. Musical learning fits neatly into that package in many ways. Musicians, especially those teaching privately, are less constricted by standardised testing and a single regimented curriculum when teaching individuals to sing or play instruments that there are a great deal of similarities, including with how we approach music learning and how children are described as approaching learning. I believe people retain at least some of that freshness and openness that is seen in young children as they grow and approach new things throughout life in learning, and playing.

CC licensed: http://bit.ly/ZHjMDT

Considering each student will yield a different result when planning that rationale for how and what is taught. Take your story about getting home. Even if you haven’t yet written it with the thought that demonstrates comprehension of the readings and explores some of the suggestions found there, you will be able to say: I get home by taking the bus. … or by driving. … or by walking. and you will know the route. Can you now translate this to a musical setting. If the journey home is uneventful and it is merely to deliver you from one place to another, How would that equate to some private lessons? What could you have noticed along the way? What took your fancy? Distracted you from simply getting from A to B? What else did you do? Who did you see?

This is all part of the musical journey, the story of the learning that makes it interesting and enjoyable for the student. The important thing is that there are these connections, a rationale for the thing that interested you on your route home.

Task:

Go back to your journey home, and replace it with the musical goals of your student.

- How are they interested and propelled forward through the different things that you include when you teach them?

- Can you musically include elements of a good story?

Make sure that the rationale behind the teaching is balanced. If one musical ingredient goes missing, or there is too much of something, the lessons may look fine, but after a time it might just go a bit wrong when it heats up and the pressure’s on….

Feel free to comment here or elsewhere, on tasks, content, or topics… I know there are no specific answers in these pages, but I hope to encourage you to think creatively and in new ways about musical learning and how you can shape what you do as a teacher. If you are on Twitter, please tag comments with #MUS654.

Pingback: Encouraging learning: A graph with perspective - lauraritchie.com